Rules, sure, but not a 'rules-based order'

Inconceivable! The 'rules-based' meme is closely tied to China narratives.

A week ago, in a fit of optimism that President Joe Biden’s departure from the US campaign could free Democrats to offer some new visions on foreign policy, I offered one simple proposal: Stop talking about the “rules-based international order.” Readers sent in a variety of feedback and references after my short post, and I wanted to share some thoughts here.

Thanks for reading Here It Comes, my newsletter on the interactions between US-China relations, technology, and climate change. All-access subscriptions are free. Readers who especially wish to support this effort, and have the means, can contribute directly through a paid subscription. I’m grateful for your attention either way. –Graham Webster

First, there is of course a place for rules in international relations, and in US policy.

I’m simply arguing that rules, or “the rules,” should not be so central to how US foreign policy thinkers and decision-makers narrate their purpose and their sense of competition with China.

It just so happened that hours before I wrote my post here, my former colleague Paul Gewirtz, director of the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School, published an essay processing what is at stake for “China, the United States, and the future of a rules-based international order.” At least for the sake of argument, he accepts the premise that the US-China moment today is indeed a “conflict about ‘the rules-based international order.’”

As I suggested last week, I reject the idea that the present US-China dynamic is overall a contest about a state of affairs undergirded by rules, because the idea that the US government is championing an order where rules govern state behavior is conspicuously undermined by the many examples of the US government violating the rules it says should constrain other states. A rules-based order? To quote Indigo Montoya, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

A basic component of the “rule of law” is that law applies to the powerful, and critics reasonably distinguish some authoritarian governance patterns as “rule by law.” A “rules-based order” is a softer concept, but if powerful states may violate rules while championing them, it’s the power and not the rules that form the base of the order. I’m advocating that politicians and strategists drop the false implication that rules are the bottom line.

The Biden administration’s central boilerplate on the China challenge actually helpfully omits “rules” and argues that it’s the “international order” that China seeks to upset:

“China is the only country with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it. Beijing’s vision would move us away from the universal values that have sustained so much of the world’s progress over the past 75 years.” –Blinken, 20221

I generally don’t blame people for discussing policy using the commonly accepted terms, even if I think they shouldn’t be the commonly accepted terms. And if we can keep “rules-based” out of it, I find much to agree with in Gewirtz’s piece. Perhaps his central contention is that the United States needs to be realistic in its efforts to, in Blinken’s terms, “revise” the international order amidst new circumstances and contention from China. He reviews a number of public statements by the Chinese government on its preferences for international norms, rules, and institutions. These cannot be ignored, because there is real power behind some of these initiatives.

None of this is to say there is no role for rules, even if they are not the basis of the order. Rules or norms of behavior that actually are followed most of the time and enforced by powerful backers keep a lot of everyday things working, and some of these are international rules and norms worked out and agreed to through the 20th century institutions many people think of when they talk about “the” international order. Global aviation, maritime safety, Internet protocols…even the UN Convention on the Law the Sea—which does not officially constrain the United States due to lack of ratification, and which China has openly flouted after a duly constituted arbitral tribunal found against it—represents a broad consensus on how to resolve trade-offs through agreed text.

Any good future for the United States, China, and others will include these and more rule-sets. The most effective possible futures for climate action I can think of would involve international agreements and rules. Recent, likely, and potential advances in machine learning have brought governments around the world to the table seeking norms or rules to avoid a variety of bad outcomes. But these potential future rules would need power behind them, probably both US and Chinese power among others, and would not based merely on an existing order.

Second, there is evidence the ‘rules-based order’ meme is fundamentally part of a China narrative and not based in sober, methodical analysis of international politics.

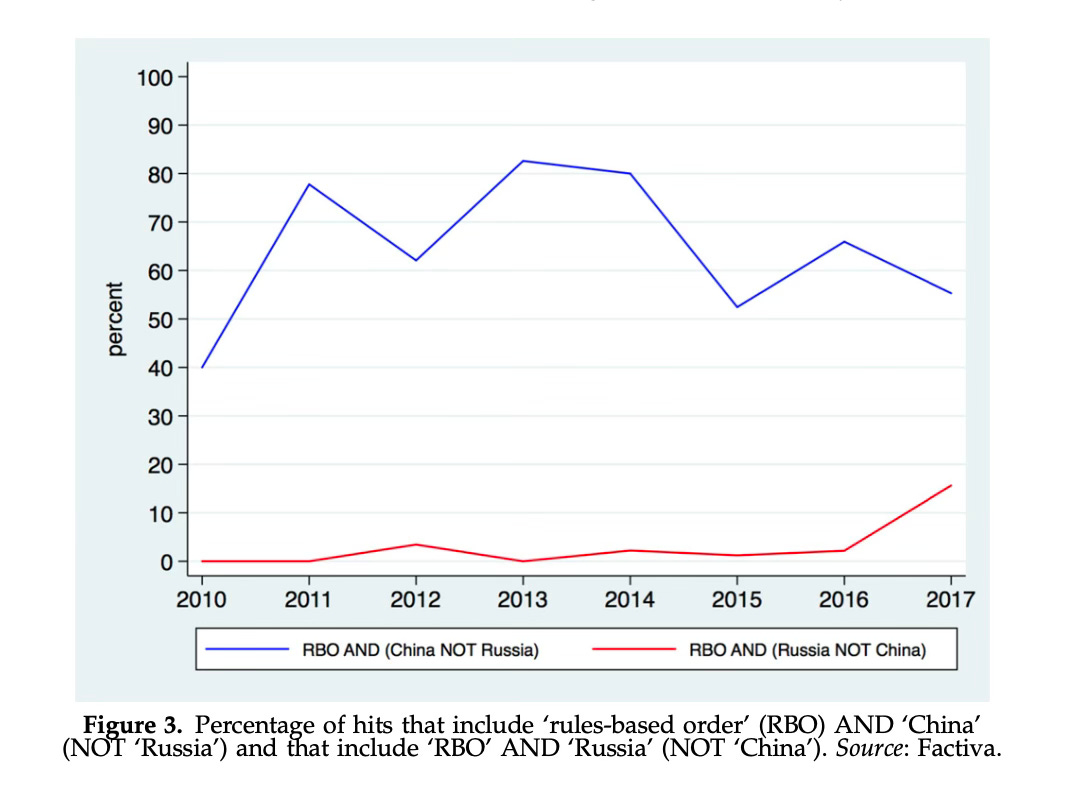

I had always encountered the “rules-based international order” in the context of US-China relations, but this should surprise no one, because I read about US-China relations every day. It turns out, as the political scientists Adam Breuer and Alastair Iain Johnston write, “the [rules-based order (RBO)] meme is almost uniquely tied to analyses of China, in contrast to other synonyms for the RBO such as the ‘liberal international order’ or the ‘liberal order’ which are less commonly used in reference to China.”2

In a 2019 article, Breuer and Johnston (disclosure: one of my teachers in grad school), set out to trace the origins of the invocation of a rules-based order. They reference academic literature on narrative construction, where memes (such as the “rules-based order”) play a role as constituent parts. A few things stand out in my reading:

As I had thought based on database searches, they find that US discourse seems to have adopted the RBO meme after its use emerged in Australian circles. They locate a meeting between then–Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd and then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2010, following which the US government used the term repeatedly. The ways in which Australian experiences with China and discourses about it have influenced US discourse and policy are widely discussed but under-studied. I find it fascinating that this meme I so strongly associate with US government self-portrayals was an import from down under.

Their media analysis suggests a strong tie between RBO language and discussions of China. From 2011–2017, consistently more than 50% of “rules-based order” mentions in their searches (in Factiva) came along with mentions of China and not Russia. Only in 2017 did the proportion of RBO mentions coming alongside Russia and not China exceed 10%. (If the RBO language were organically based in respect for international rules such as territorial sovereignty, I would have expected Russia to rank higher after its 2014 invasion of Ukraine.)

There’s a rich field of associations to unpack around the idea of an RBO and its resonance. They observe that “[f]air play is an element in American exceptionalism. … Newt Gingrich has identified ‘Rule of Law’ and its component ‘Honoring Principles of Fair Play and Justice’ as central to American exceptionalism. Thus, for some, challenging an RBO means challenging the American exceptionalist trait of fair play.” Indeed, in the same era the RBO or RBIO became a popular refrain, it was also common to talk about “a level playing field” in economics. Breuer and Johnston talk about other sub-narratives, around law breaking, Chinese trickery, etc. And they argue that these sub-narratives and memes “help constitute and empower a master narrative about China’s revisionism.” There’s more in the paper.

The paper’s effort to place the “rules-based” meme within a structure of narratives using fairly simple empirical observations helps underline the fact that political and diplomatic language around international affairs is rarely especially concrete, specific, or dryly literal. It’s about storylines, what stories are officially basic truths, and the bounds of discussion that allow one to be taken seriously. It’s an important reminder that these narratives play on stories people have about themselves, their countries, and others and are not manufactured in some scientific laboratory discovering laws of history.

###

As always, thanks for reading. If you have not subscribed, please do. If you wish to support this effort and have the means, please consider a paid subscription.

About Here It Comes

Here it Comes is written by me, Graham Webster, a research scholar and editor-in-chief of the DigiChina Project at the Stanford Program on Geopolitics, Technology, and Governance. It is the successor to my earlier newsletter efforts U.S.–China Week and Transpacifica. Here It Comes is an exploration of the onslaught of interactions between US-China relations, technology, and climate change. The opinions expressed here are my own, and I reserve the right to change my mind.

While Blinken here and some of the administration’s central strategic documents do not say “rules-based,” his department website reveals dozens of uses of the term, many in multilateral contexts where China is a key focus, such as the Quad. See, e.g. this Google search.

Adam Breuer & Alastair Iain Johnston (2019) Memes, narratives and the emergent US–China security dilemma, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32:4, 429-455, DOI: 10.1080/09557571.2019.1622083