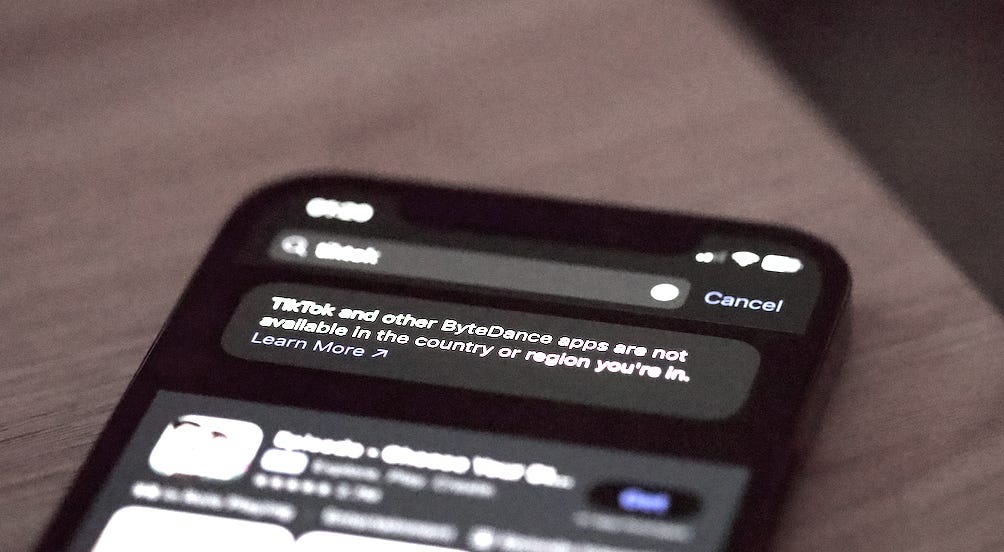

China shows it will always have a say in a TikTok deal

Reuters and NPR report US tariffs led the Chinese government to block a pending deal

Trump today said he was extending the TikTok deal timeline by 75 days, regardless of whether he can do that legally. More interesting perhaps, Reuters reported that “a deal to spin off U.S. assets was put on hold after China indicated it would not approve the deal following” Trump’s tariffs this week.

On Bluesky, NPR’s Bobby Allyn confirmed: “all sides agreed on a TikTok deal, but after tariffs, China indicated to ByteDance it would not be signing off on the agreement. I’m told China will be holding deal hostage until they can extract some kind of concessions.”

Allyn has more: “The deal was structured to allow BD to own and maintain TikTok's algorithm. The new U.S. entity was set to license the algorithm from BD.,” Allyn wrote. “Was thought this would circumvent export-control laws, which are open to Beijing's interpretation. In wake of tariffs, China changed its stance on this.”

A few thoughts.

This makes it clear that, despite Trump styling himself as the dealmaker, “all sides” includes the Chinese government. No path forward is unobstructed without their consent.

It’s important to maintain a healthy skepticism about how close a deal really was, if Chinese government sign-off was not locked. Anyone who was saying it was done or nearly done—their versions of events need to be properly discounted.

If dealmakers thought they were going to avoid Chinese government scrutiny by licensing, rather than purchasing or transferring, the algorithm, they are not as clever as they thought they were. Much attention has been paid to the inclusion of recommendation algorithms on a catalogue of items that may be subject to export controls.1 But this specific legal mechanism is not the crucial point. China’s government has both legal and extralegal tools at its disposal to stop any deal if it wishes.

There are probably even more direct legal levers I’m not thinking of, but another one comes to mind. The Data Security Law in Article 26 states that “the PRC may take reciprocal measures” against any country that “adopts discriminatory prohibitions, restrictions, or other similar measures against the PRC relevant to investment, trade, etc., in data, data development and use technology, etc.” What is a discriminatory prohibition, restriction, etc.? That’s up to the state. What kind of reciprocal measures might be taken? Unspecified. This is a provision sitting there to hit back when China’s government judges that it has been hit and using this provision would be convenient. There are others.

Meanwhile, legal or not, ByteDance knows it can’t just disregard the state’s preferences if it wants to keep making gobs of money. See what happened to AliPay when Jack Ma resisted the state’s financial regulatory vision, or to DiDi when it went forward with an IPO after being told not to. Chinese firms are not all arms of the party-state, contrary to popular DC talking points, but they are subject to party-state’s exercise of power, legally or otherwise.

Meanwhile, back in the swamp, licensing an algorithm maintained by ByteDance, as Bill Bishop recently noted, appears to be a flagrant violation of the TikTok divest-or-ban law. The “qualified divestiture” that the president must determine has happened to avoid the ban “precludes the establishment or maintenance of any operational relationship between the United States operations of the relevant foreign adversary controlled application … including any cooperation with respect to the operation of a content recommendation algorithm.” Pretty darn clear.

In this whole discussion, the definition of an algorithm, or a “content generation algorithm” or a “personalized information push service technology based on data analysis” is vague. The specific architecture of the MacGuffin in this drama really does matter. I think it’s unlikely, but if the “algorithm” were frozen in time and licensed, never to be updated by ByteDance but never getting “exported,” maybe they would have found their hack. (It’s beyond my knowledge and the scope of this post to assess whether licensing would count as an export, but I do welcome experts to weigh in!) Anyway, Chinese government leverage discussed in item 3 above would still be present.

It’s a US legal expert question what kind of risk Apple and Google and TikTok’s infrastructure vendors would be exposed to if they move forward in violation of the letter of the law but with explicit presidential blessing. But it still seems pretty risky to me, given the capriciousness of this president and the fact that, generally, we do change presidents in the United States.

If somehow a deal like the one being described goes through, US government oversight on the algorithmic manipulation and data security risks motivating the law will likely be less than would have occurred under Project Texas. We never got full details, but the proposal as reported by people who were briefed by TikTok included a bunch of government auditing and supervisory structures.

Whatever happens with TikTok, whether a deal goes through contrary to the law, or even if a ban is enacted or a truly “qualified divestiture” takes place, this whole saga will at best have only addressed the national security, privacy, and algorithmic manipulations of one app. Threats to US users’ privacy, bad behavior in the market, national security where it is implicated—the whole range of TikTok concerns and more—remain broadly unaddressed if the app at issue is not TikTok. Thats why, for years, I and others have advocated a regulatory approach that covers all services.

That’s all for now. Signing off for the weekend.

About Here It Comes

Here it Comes is written by me, Graham Webster, a research scholar and editor-in-chief of the DigiChina Project at the Stanford Program on Geopolitics, Technology, and Governance. It is the successor to my earlier newsletter efforts U.S.–China Week and Transpacifica. Here It Comes is an exploration of the onslaught of interactions between US-China relations, technology, and climate change. The opinions expressed here are my own, and I reserve the right to change my mind.

The relevant bit is on the list of limited items, sector 96, item 18, on the second to last page of the doc: “基于数据分析的个性化信息推送服务技术 (基于海量数据持续训练优化的用户个性化偏好学习技术、 用户个性化偏好实时感知技术、 信息内容特征建模技术、 用户偏好与信息内容匹配分析技术、 用于支撑推荐算法的大规模分布式实时计算技术等).” Item 16 is also cited in at least one commentary as a relevant controlled item: “专门用于汉语及少数民族语言的人工智能交互界面技术” (Specialized artificial intelligence interactive interface technology using Chinese or [PRC] minority ethnicity languages.” https://images.mofcom.gov.cn/fms/202312/20231221153855374.pdf